Both an eventful and uneventful few days. After a morning reading Mercia

Eliade’s classic text, The Sacred and the Profane, soaking up the

sunshine at Nazca, I took the long bus journey back to Lima – the bus

arrived late and made a number of unscheduled stops (including for the

driver to buy some oranges from a roadside vendor) arriving in Lima

80minutes late. My restaurant of choice was fully booked by then, and

arriving by taxi at the alternative I found it too was fully booked,

despite the Hotel receptionist shrugging that I would not need to book

there. They took pity on me though and put me on a bar stool at the

bar, where I enjoyed a fabulous meal, generosity from the talkative

barman, and a thoroughly good Saturday night out. I can thoroughly

recommend the Brujas de Cachiche to any visitor to Lima.

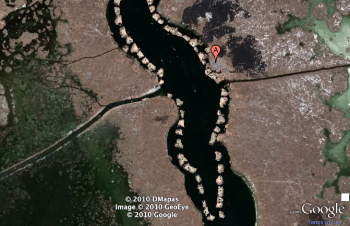

Sunday was then all about flying up to the mountains – an airbus from

Lima airport at lunchtime stopping over briefly at Cusco, without

disembarking, and then heading on up to Juliaca, the small city on the

plain overlooking Lake Titicaca. From the moment I got off the plane I

could tell we were very high up, and that the air was thin! Walking

suddenly became a struggle, and the effort of any exertion seriously

taxing on one’s reserves of strength. This immediate fatigue receeded

in the car, replaced by consciousness of having to breathe really

quickly – a shortness of breath one would normally associate with the

moments after major exertion, but experienced whilst sitting in the back

seat of the guide’s car. On the way to my hotel in Puno, we stopped to

visit the Silustani Tombs.

This proved to be a fascinating visit, despite the fact that I was only

capable of pigeon-toe progress with frequent rest-stops, and the fatigue

was gradually turning into a dizziness of absolute exhaustion. But the

history of this area, as my guide described it, was fascinating. The

Pucara people were the first known civilisation here, and I will see

more of them on the Inka Express bus journey to Puno later this week.

After this culture had faded, the Tihuanaco came, and populated the

area. At the height of their civilisation here, the Aymara, a warlike

people from the south and east, perhaps Argentina, conquered the area,

forcing the small remnant of surviving Tihuanaco to embark on a long

wandering in the mountains, until they settled north in the sacred

valley, and became the Inca. The Inca, of course, later reconquered

this area, along with the whole of the rest of the Andes, in the largest

empire of all pre-Columbian South America – of which more, of course,

in Cusco and Macchu Picchu. Up here in Juliaca and Puno, despite the

arrival of the Spanish conquerors, who looted the ancient sites and

brought Catholicism to the area, much of the original pre-Christian

religious practice and the two ‘nations’, Aymara and Quechua

(Inca/Tihuanaco people) survive to this day. My guide is Quechua, the

driver Aymara.

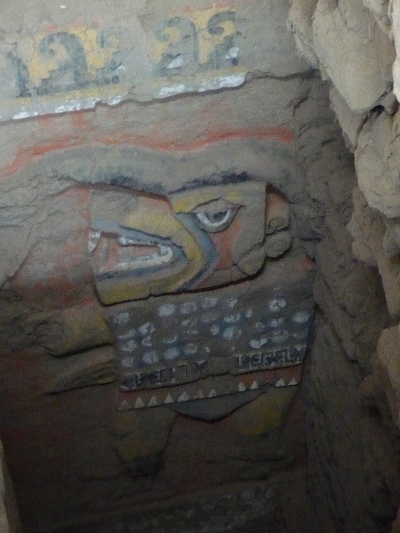

The Silustani tombs are mostly Aymara, with some later Inca tombs as

well. Alongside the tombs are three other sections of the site: the

ritual area, the workshop, storage and living area, and the quarry where

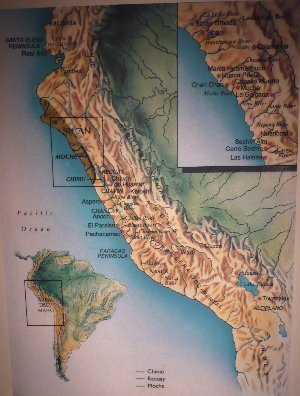

the rock was carved out of the mountainside. Like the Moche practice

in the far north, and Egyptian and other practices in other continents,

not only the Lord but his wives, boys, servants, priests – between 30

and 50 bodies – were buried in each of the tombs. All the precious

metal artefacts were looted by the Spanish, but archaeologists have

found ample evidence of human bones, ceramics and other remants to gain

understanding of these monuments.

The largest of them, an Inca one, with exquisite stone work, also had a

relief carving of a lizard on it, pointing in the direction of the

Temple of the Sun, the island on the Bolivian side of the lake where the

Inca absorbed the Tihuanaco origin myth and made it their own, with a

splendid temple.

In the ritual area, I was introduced to a very familiar stone circle.

My guide clearly had real respect for the place: he pointed out on the

horizon to south and east among the mountains where the villages of his

mother and father were located, and spoke with genuine appreciation of

the Quechua Mother Earth ‘Pacha Mama’ and Mother Waters ‘Cucha Mama’

whose spirits were in everything, in every stone. The archaic religious

mind, as described by Mercia Eliade, was here almost in its raw aspect,

for all that this son of tribal people now worked in the tourist

industry, using his excellent English. Having asked permission, I

entered the stone circle, and paid my respects to the Earth Mother of

the Mountain, here at the roof of the world, my body the tree through

which earth and sky communicate and become one, pillar of every house,

tower of every city, altar of every temple.

On the descent from the hill of the tombs, though the thin air was

really starting to get to me by now, (hence the not very good photo) my

guide showed me the guardian stone at the foot of the ancient stairway.

He asked me if I had a compass. A spiral carved on one side of the rock

zeroed in on a particular patch of the stone where the compass on my

iPhone suddenly switched to point west, instead of north, directly at

the centre of the spiral. Yes, indeed they believe there is some

lodestone or other in this rock, and yes, indeed, the Aymara clearly

knew about this. The other side of the rock sported the carved face of a

Puma, facing up to the stones.

But my reaction to the thin air was rapidly turning into full-on Acute Mountain Sickness (AMS),

or altitude sickness, and we headed on to Puno as the sun went down and

the cold wind of the mountain winter began to bring the temperature

down sharply. At the hotel I practically collapsed for an hour or two’s

nap, and then managed to pigeon-toe down to the nearest restaurant, a

couple of doors down from the hotel, for a light supper, and pigeon-toe

it back up to my room, completely exhausted, to sleep again. It was

9pm. I awoke almost hourly, drinking water, feeling exhausted, my pulse

rapid and persistent, breathing short, dizzy and suffering awful

fatigue. Finally, at about 4am, the pulse and shortness of breath had

begun to recede, to be replaced by a headache. I took some ibuprofen at

5am, and finally decided to cancel my tour to the Lake Titicaca

Islands, to stay put and get a day of complete rest. By 9am, worried

for me, the travel agency had called in CondorAssist, the medical

insurance with my fortnight’s tour, and a very nice young Quechua doctor

arrived, with a translator. It was agreed by all that it was altitude

sickness, that the worst was over, that I had done the right thing

cancelling today’s tour, and he sat me with an oxygen mask plugged into

an oxygen bottle that they keep at the hotel, for 20 minutes, which

cleared my headache!

By lunchtime I was able to take a little walk, buy some alpaca socks and

a straw sun hat, and get a bowl of Inca Soup – guinea pig and alpaca

meat and soft cheese cubes in a nourishing soup, which I ate most of

with a large glass of freshly juiced papaya. It is interesting how, up

here in the mountains, many of the local people still maintain the

traditional dress, at the same time as embracing the all-encompassing

information revolution. This excursion, however, was very tiring, and I

returned, again very slowly to the hotel, to sleep for a couple of

hours in the afternoon.

So – not only do I get air-sick on little Cessna’s doing wild

manouevres, I am among those who suffer from altitude sickness, too.

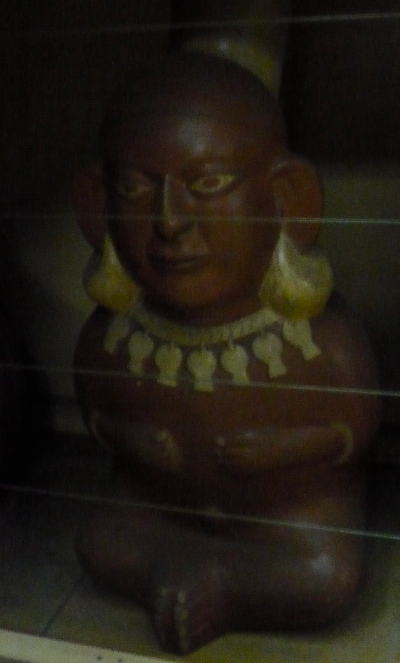

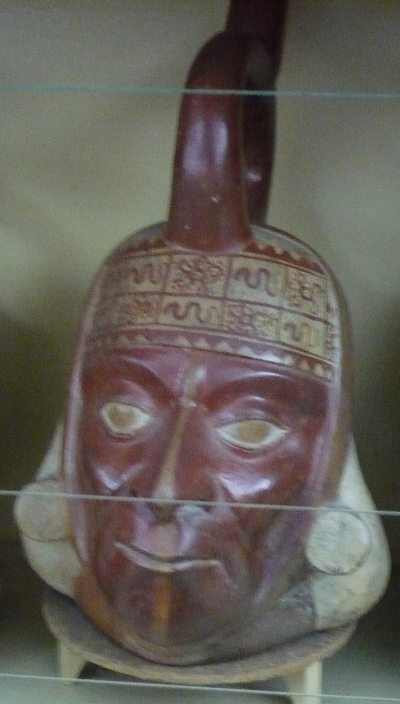

The Inka Express is an extremely long bus ride – usually a 6hr drive – which takes over 9hrs, due to all the stops along the way. But time goes quickly, and it doesn’t seem to drag, as a journey, at all. Leaving Puno, barely having slept, with an altitude headache only partly dulled by 10minutes attached to the oxygen bottle before getting up, jacked up on matte de coca (coca-leaf tea) I half expected the journey to be awful. But I managed to dose during the first part of the journey, awaking to be delighted by the Pukara museum, sporting a whole collection of statuary from the ‘mother culture’ of southern Peru, who lived here around 400BCE. The catfish and the frog turned out to be particularly important animals for these people, but the puma and the snake made early appearances – they both figure heavily in later cultures – and the quality of the carving is really quite special.

The Inka Express is an extremely long bus ride – usually a 6hr drive – which takes over 9hrs, due to all the stops along the way. But time goes quickly, and it doesn’t seem to drag, as a journey, at all. Leaving Puno, barely having slept, with an altitude headache only partly dulled by 10minutes attached to the oxygen bottle before getting up, jacked up on matte de coca (coca-leaf tea) I half expected the journey to be awful. But I managed to dose during the first part of the journey, awaking to be delighted by the Pukara museum, sporting a whole collection of statuary from the ‘mother culture’ of southern Peru, who lived here around 400BCE. The catfish and the frog turned out to be particularly important animals for these people, but the puma and the snake made early appearances – they both figure heavily in later cultures – and the quality of the carving is really quite special.

The hostess at the Myers Inn, however, told me a wonderful story of how the logging company wanted to take out a whole part of the forest, and all the womens’ clubs and institutes in the region got together to protest, and raise the cash to buy this part of the forest, and grant it to the National Park. This area is now called the Womens’ Grove, and includes the mysterious Albino Tree, which, according to my hostess, was known by the ‘Indians’ as the ‘Spirit of the Forest’. I love this other America. I can’t say I got much spiritual communication from this genetic deformity, however – it was simply a very unusual brilliant white fir tree – an natural oddity.

The hostess at the Myers Inn, however, told me a wonderful story of how the logging company wanted to take out a whole part of the forest, and all the womens’ clubs and institutes in the region got together to protest, and raise the cash to buy this part of the forest, and grant it to the National Park. This area is now called the Womens’ Grove, and includes the mysterious Albino Tree, which, according to my hostess, was known by the ‘Indians’ as the ‘Spirit of the Forest’. I love this other America. I can’t say I got much spiritual communication from this genetic deformity, however – it was simply a very unusual brilliant white fir tree – an natural oddity. Further up the Avenue of the Giants there are indeed some really big trees – the Tall Tree, at 360ft apparently something like the ninth tallest living thing on Earth (the others are in Redwood National Forest, to the north, and in China, where the other remaining Redwoods live.) Walking alone in this part of the forest one really gets a sense of the ancient woods of the world – something almost pre-mammalian, let alone pre-human, ancient, almost other-worldly.

Further up the Avenue of the Giants there are indeed some really big trees – the Tall Tree, at 360ft apparently something like the ninth tallest living thing on Earth (the others are in Redwood National Forest, to the north, and in China, where the other remaining Redwoods live.) Walking alone in this part of the forest one really gets a sense of the ancient woods of the world – something almost pre-mammalian, let alone pre-human, ancient, almost other-worldly.